Continued fraction

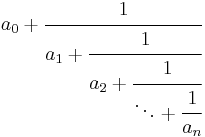

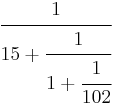

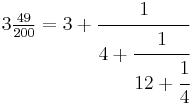

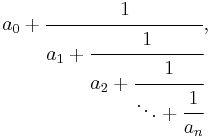

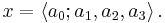

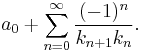

Finite continued fraction, where a0 is an integer, any other ai are positive integers, and n is a non-negative integer.

In mathematics, a continued fraction is an expression obtained through an iterative process of representing a number as the sum of its integer part and the reciprocal of another number, then writing this other number as the sum of its integer part and another reciprocal, and so on.[1] In a finite continued fraction (or terminated continued fraction), the iteration/recursion is terminated after finitely many steps by using an integer in lieu of another continued fraction. In contrast, an infinite continued fraction is an infinite expression. In either case, all integers in the sequence, other than the first, must be positive.

Continued fractions have a number of remarkable properties related to the Euclidean algorithm for integers or real numbers. Every rational number p/q has two closely related expressions as a finite continued fraction, whose coefficients ai can be determined by applying the Euclidean algorithm to (p,q). The numerical value of an infinite continued fraction will be irrational; it is defined from its infinite sequence of integers as the limit of a sequence of values for finite continued fractions. Each finite continued fraction of the sequence is obtained by using a finite prefix of the infinite continued fraction's defining sequence of integers. Moreover, every irrational number α is the value of a unique infinite continued fraction, whose coefficients can be found using the non-terminating version of the Euclidean algorithm applied to the incommensurable values α and 1. This way of expressing real numbers (rational and irrational) is called their continued fraction representation.

If arbitrary values and/or functions are used in place of one or more of the numerators or the integers in the denominators, the resulting expression is a generalized continued fraction. When it is necessary to distinguish the first form from generalized continued fractions, the former may be called a simple or regular continued fraction, or said to be in canonical form.

The term continued fraction may also refer to representations of rational functions, arising in their analytic theory. For this use of the term see Padé approximation and Chebyshev rational functions.

Motivation and notation

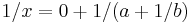

Consider a typical rational number 415/93, which is around 4.4624. As a first approximation, start with 4, which is the integer part. Note that the fractional part is the reciprocal of 93/43 which is about 2.1628. Use the integer part, 2, as an approximation for the reciprocal, to get a second approximation of 4 + 1/2 = 4.5. The fractional part of 93/43 is the reciprocal of 43/7 which is about 6.1429. Use 6 as an approximation for this to get 2 + 1/6 as an approximation for 93/43 and 4 + 1/(2 + 1/6), about 4.4615, as the third approximation. Finally, the fractional part of 43/7 is the reciprocal of 7, so its approximation in this scheme, 7, is exact and produces the exact expression 4+1/(2+1/(6+1/7)) for 415/93. This expression is called the continued fraction representation of the number. Dropping some of the less essential parts of the expression 4 + 1 / (2 + 1 / (6 + 1 / 7)) gives the abbreviated notation 415/93=[4;2,6,7]. Note that it is customary to replace only the first comma by a semicolon. Some older textbooks use all commas in the (n + 1)-tuple, e.g. [4,2,6,7].[2][3]

If the starting number is rational then this process exactly parallels the Euclidean algorithm. In particular, it must terminate and produce a finite continued fraction representation of the number. If the starting number is irrational then the process continues indefinitely. This produces a sequence of approximations, all of which are rational numbers, and these converge to the starting number as a limit. This is the (infinite) continued fraction representation of the number. Examples of continued fraction representations of irrational numbers are:

- √19 = [4;2,1,3,1,2,8,2,1,3,1,2,8,…]. The pattern repeats indefinitely with a period of 6.

- e = [2;1,2,1,1,4,1,1,6,1,1,8,…] (sequence A003417 in OEIS). The pattern repeats indefinitely with a period of 3 except that 2 is added to one of the terms in each cycle.

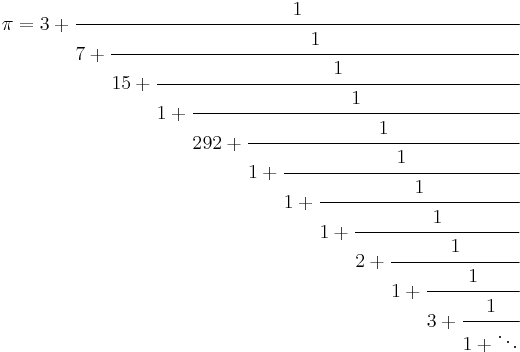

- π = [3;7,15,1,292,1,1,1,2,1,3,1,…] (sequence A001203 in OEIS). The terms in this representation are apparently random.

Continued fractions are, in some ways, more "mathematically natural" representations of real number than other representations such as decimal representations, and they have several desirable properties:

- The continued fraction representation for a rational number is finite and only rational numbers have finite representations. In contrast, the decimal representation of a rational number may be finite, for example 137/1600=0.085625, or infinite with a repeating cycle, for example 4/27=0.148148148148….

- Every rational number has an essentially unique continued fraction representation. Each rational can be represented in exactly two ways, since [a0; a1, … an − 1, an] = [a0; a1, … an − 1, an − 1, 1]. Usually the first, shorter one is chosen as the canonical representation.

- The continued fraction representation of an irrational number is unique.

- The real numbers whose continued fraction eventually repeats are precisely the quadratic irrationals.[4] For example, the repeating continued fraction [1; 1, 1, 1, …] is the golden ratio, and the repeating continued fraction [1; 2, 2, 2, …] is the square root of 2. In contrast, the decimal representations of quadratic irrationals are apparently random.

- The successive approximations generated in finding the continued fraction representation of a number, i.e. by truncating the continued fraction representation, are in a certain sense (described below) the "best possible".

Basic formulae

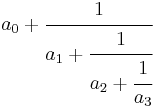

A finite continued fraction is an expression of the form

where  0 is an integer, any other

0 is an integer, any other  members are positive integers, and

members are positive integers, and  is a non-negative integer.

is a non-negative integer.

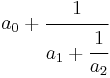

Thus, all of the following illustrate valid finite continued fractions:

| Formula | Numeric | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

|

|

All integers are a degenerate case |

|

|

Simplest possible fractional form |

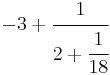

|

|

First integer may be negative |

|

|

First integer may be zero |

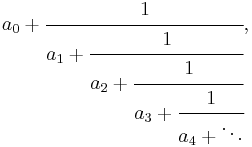

An infinite continued fraction can be written as

with the same same constraints on the  as in the finite case.

as in the finite case.

Calculating continued fraction representations

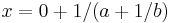

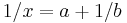

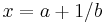

Consider a real number r. Let i be the integer part and f the fractional part of r. Then the continued fraction representation of r is [i; a1, a2,...], where [a1; a2,...] is the continued fraction representation of 1/f.

To calculate a continued fraction representation of a number r, write down the integer part (technically the floor) of r. Subtract this integer part from r. If the difference is 0, stop; otherwise find the reciprocal of the difference and repeat. The procedure will halt if and only if r is rational.

-

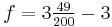

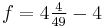

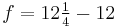

Find the continued fraction for 3.245 (=  )

)Step Real Number Integer part Fractional part Simplified Reciprocal of

Simplified

STOP Continued fraction form for 3.245 or  is [3; 4, 12, 4]

is [3; 4, 12, 4]

The number 3.245 can also be represented by the continued fraction expansion [3; 4, 12, 3, 1]; refer to Finite continued fractions below.

Notations for continued fractions

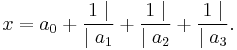

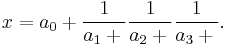

The integers a0, a1, etc., are called the quotients of the continued fraction. One can abbreviate a continued fraction as

or, in the notation of Pringsheim, as

Here is another related notation:

Sometimes angle brackets are used, like this:

The semicolon in the square and angle bracket notations is sometimes replaced by a comma.

One may also define infinite simple continued fractions as limits:

This limit exists for any choice of a0 and positive integers a1, a2, ... .

Finite continued fractions

Every finite continued fraction represents a rational number, and every rational number can be represented in precisely two different ways as a finite continued fraction. These two representations agree except in their final terms. In the longer representation the final term in the continued fraction is 1; the shorter representation drops the final 1, but increases the new final term by 1. The final element in the short representation is therefore always greater than 1, if present. In symbols:

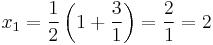

For example,

Continued fractions of reciprocals

The continued fraction representations of a positive rational number and its reciprocal are identical except for a shift one place left or right depending on whether the number is less than or greater than one respectively. In other words, the numbers represented by ![[a_0;a_1,a_2,a_3,\ldots,a_n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/371951e599137b2a4dc77b15f08da9f7.png) and

and ![[0;a_0,a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ec441968137bb5480ee35884c3ceea36.png) are reciprocals. This is because if

are reciprocals. This is because if  is an integer then if

is an integer then if  then

then  and

and  and if

and if  then

then  and

and  with the last number that generates the remainder of the continued fraction being the same for both

with the last number that generates the remainder of the continued fraction being the same for both  and its reciprocal.

and its reciprocal.

For example,

Infinite continued fractions

Every infinite continued fraction is irrational, and every irrational number can be represented in precisely one way as an infinite continued fraction.

An infinite continued fraction representation for an irrational number is mainly useful because its initial segments provide excellent rational approximations to the number. These rational numbers are called the convergents of the continued fraction. Even-numbered convergents are smaller than the original number, while odd-numbered ones are bigger.

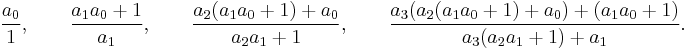

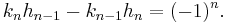

For a continued fraction [a0; a1, a2, ...], the first four convergents (numbered 0 through 3) are

In words, the numerator of the third convergent is formed by multiplying the numerator of the second convergent by the third quotient, and adding the numerator of the first convergent. The denominators are formed similarly. Therefore, each convergent can be expressed explicitly in terms of the continued fraction as the ratio of certain multivariate polynomials called continuants.

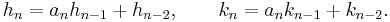

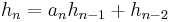

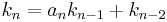

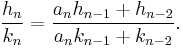

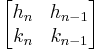

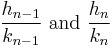

If successive convergents are found, with numerators h1, h2, ... and denominators k1, k2, ... then the relevant recursive relation is:

The successive convergents are given by the formula

Thus to incorporate a new term into a rational approximation, only the two previous convergents are necessary. The initial "convergents" (required for the first two terms) are 0⁄1 and 1⁄0. For example, here are the convergents for [0;1,5,2,2].

-

n −2 −1 0 1 2 3 4 an 0 1 5 2 2 hn 0 1 0 1 5 11 27 kn 1 0 1 1 6 13 32

When using the Babylonian method to generate successive approximations to the square root of an integer, if one starts with the lowest integer as first approximant, the rationals generated all appear in the list of convergents for the continued fraction. Specifically, the approximants will appear on the convergents list in positions 0, 1, 3, 7, 15, ...,  ... For example, the continued fraction expansion for

... For example, the continued fraction expansion for  is [1; 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, ...]. Comparing the convergents with the approximants derived from the Babylonian method:

is [1; 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, ...]. Comparing the convergents with the approximants derived from the Babylonian method:

-

n −2 −1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 an 1 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 hn 0 1 1 2 5 7 19 26 71 97 kn 1 0 1 1 3 4 11 15 41 56

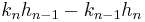

Some useful theorems

If a0, a1, a2, ... is an infinite sequence of positive integers, define the sequences  and

and  recursively:

recursively:

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Theorem 1

For any positive

Theorem 2

The convergents of [a0; a1, a2, ...] are given by

Theorem 3

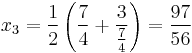

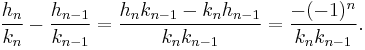

If the nth convergent to a continued fraction is  , then

, then

Corollary 1: Each convergent is in its lowest terms (for if  and

and  had a nontrivial common divisor it would divide

had a nontrivial common divisor it would divide  , which is impossible).

, which is impossible).

Corollary 2: The difference between successive convergents is a fraction whose numerator is unity:

Corollary 3: The continued fraction is equivalent to a series of alternating terms:

Corollary 4: The matrix

has determinant plus or minus one, and thus belongs to the group of 2x2 unimodular matrices  .

.

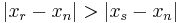

Theorem 4

Each (sth) convergent is nearer to a subsequent (nth) convergent than any preceding (rth) convergent is. In symbols, if the nth convergent is taken to be ![[a_0;a_1,a_2,\ldots a_n]=x_n](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ae1e4ae3bd78e70fbdfdcd86423f72d8.png) , then

, then

for all r < s < n.

Corollary 1: the even convergents (before the nth) continually increase, but are always less than xn.

Corollary 2: the odd convergents (before the nth) continually decrease, but are always greater than xn.

Theorem 5

Corollary 1: any convergent is nearer to the continued fraction than any other fraction whose denominator is less than that of the convergent

Corollary 2: any convergent which immediately precedes a large quotient is a near approximation to the continued fraction.

Semiconvergents

If

are successive convergents, then any fraction of the form

where a is a nonnegative integer and the numerators and denominators are between the n and n + 1 terms inclusive are called semiconvergents, secondary convergents, or intermediate fractions. Often the term is taken to mean that being a semiconvergent excludes the possibility of being a convergent, rather than that a convergent is a kind of semiconvergent.

The semiconvergents to the continued fraction expansion of a real number x include all the rational approximations which are better than any approximation with a smaller denominator. Another useful property is that consecutive semiconvergents a/b and c/d are such that ad − bc = ±1.

Best rational approximations

A best rational approximation to a real number x is a rational number n/d, d > 0, that is closer to x than any approximation with a smaller denominator. The simple continued fraction for x generates all of the best rational approximations for x according to three rules:

- Truncate the continued fraction, and possibly decrement its last term.

- The decremented term cannot have less than half its original value.

- If the final term is even, half its value is admissible only if the corresponding semiconvergent is better than the previous convergent. (See below.)

For example, 0.84375 has continued fraction [0;1,5,2,2]. Here are all of its best rational approximations.

-

[0;1] [0;1,3] [0;1,4] [0;1,5] [0;1,5,2] [0;1,5,2,1] [0;1,5,2,2] 1

The strictly monotonic increase in the denominators as additional terms are included permits an algorithm to impose a limit, either on size of denominator or closeness of approximation.

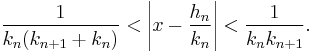

The "half rule" mentioned above is that when ak is even, the halved term ak/2 is admissible if and only if ![| x - [a_0�; a_1, \dots, a_{k-1}] | > | x - [a_0�; a_1, \dots, a_{k-1}, a_k/2]|.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0ac6003c6686cd05e5a2ca1291fa743f.png) [5] This is equivalent[5] to:

[5] This is equivalent[5] to:

The convergents to x are best approximations in an even stronger sense: n/d is a convergent for x if and only if |dx − n| is the least relative error among all approximations m/c with c ≤ d; that is, we have |dx − n| < |cx − m| so long as c < d. (Note also that |dkx − nk| → 0 as k → ∞.)

Best rational within an interval

A rational that falls within the interval  , for

, for  , can be found with the continued fractions for

, can be found with the continued fractions for  and

and  . When both

. When both  and

and  are irrational and

are irrational and

where  and

and  have identical continued fraction expansions up through

have identical continued fraction expansions up through  , a rational that falls within the interval

, a rational that falls within the interval  is given by the finite continued fraction,

is given by the finite continued fraction,

This rational will be best in that no other rational in (x,y) will have a smaller numerator or a smaller denominator.

If  is rational, it will have two continued fraction representations that are finite,

is rational, it will have two continued fraction representations that are finite,  and

and  , and similarly a rational

, and similarly a rational  will have two representations,

will have two representations,  and

and  . The coefficients beyond the last in any of these representations should be interpreted as +∞; and the best rational will be one of

. The coefficients beyond the last in any of these representations should be interpreted as +∞; and the best rational will be one of  ,

,  ,

,  , or

, or  .

.

For example, the decimal representation 3.1416 could be rounded from any number in the interval ![[3.14155, 3.14165]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f55dbca0b8edf29003dcec62e5eea72a.png) . The continued fraction representations of 3.14155 and 3.14165 are

. The continued fraction representations of 3.14155 and 3.14165 are

and the best rational between these two is

Thus, in some sense, 355/113 is the best rational number corresponding to the rounded decimal number 3.1416.

Interval for a convergent

A rational number, which can be expressed as finite continued fraction in two ways,

will be one of the convergents for the continued fraction expansion of a number, if and only if the number is strictly between

Note that the numbers  and

and  are formed by incrementing the last coefficient in the two representations for

are formed by incrementing the last coefficient in the two representations for  , and that

, and that  when

when  is even, and

is even, and  when

when  is odd.

is odd.

For example, the number 355/113 has the continued fraction representations

and thus 355/113 is a convergent of any number strictly between

Comparison of continued fractions

Consider x = [a0; a1, ...] and y = [b0; b1, ...]. If k is the smallest index for which ak is unequal to bk then x < y if (−1)k(ak − bk) < 0 and y < x otherwise.

If there is no such k, but one expansion is shorter than the other, say x = [a0; a1, ..., an] and y = [b0; b1, ..., bn, bn+1, ...] with ai = bi for 0 ≤ i ≤ n, then x < y if n is even and y < x if n is odd.

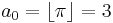

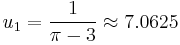

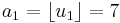

Continued fraction expansions of π

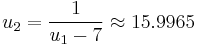

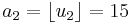

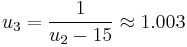

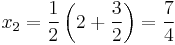

To calculate the convergents of pi we may set  , define

, define  and

and  ,

,  and

and  ,

,  . Continuing like this, one can determine the infinite continued fraction of π as

. Continuing like this, one can determine the infinite continued fraction of π as

- [3; 7, 15, 1, 292, 1, 1, ...] (sequence A001203 in OEIS).

The third convergent of π is [3; 7, 15, 1] = 355/113 = 3.14159292035..., sometimes called Milü, which is fairly close to the true value of π.

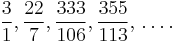

Let us suppose that the quotients found are, as above, [3; 7, 15, 1]. The following is a rule by which we can write down at once the convergent fractions which result from these quotients without developing the continued fraction.

The first quotient, supposed divided by unity, will give the first fraction, which will be too small, namely, 3/1. Then, multiplying the numerator and denominator of this fraction by the second quotient and adding unity to the numerator, we shall have the second fraction, 22/7, which will be too large. Multiplying in like manner the numerator and denominator of this fraction by the third quotient, and adding to the numerator the numerator of the preceding fraction, and to the denominator the denominator of the preceding fraction, we shall have the third fraction, which will be too small. Thus, the third quotient being 15, we have for our numerator (22 × 15 = 330) + 3 = 333, and for our denominator, (7 × 15 = 105) + 1 = 106. The third convergent, therefore, is 333/106. We proceed in the same manner for the fourth convergent. The fourth quotient being 1, we say 333 times 1 is 333, and this plus 22, the numerator of the fraction preceding, is 355; similarly, 106 times 1 is 106, and this plus 7 is 113.

In this manner, by employing the four quotients [3; 7, 15, 1], we obtain the four fractions:

These convergents are alternately smaller and larger than the true value of π, and approach nearer and nearer to π. The difference between a given convergent and π is less than the reciprocal of the product of the denominators of that convergent and the next convergent. For example, the fraction 22/7 is greater than π, but 22/7 − π is less than 1/(7×106), that is 1/742 (in fact, 22/7 − π is just less than 1/790).

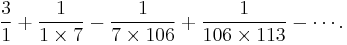

The demonstration of the foregoing properties is deduced from the fact that if we seek the difference between one of the convergent fractions and the next adjacent to it we shall obtain a fraction of which the numerator is always unity and the denominator the product of the two denominators. Thus the difference between 22/7 and 3/1 is 1/7, in excess; between 333/106 and 22/7, 1/742, in deficit; between 355/113 and 333/106, 1/11978, in excess; and so on. The result being, that by employing this series of differences we can express in another and very simple manner the fractions with which we are here concerned, by means of a second series of fractions of which the numerators are all unity and the denominators successively be the product of every two adjacent denominators. Instead of the fractions written above, we have thus the series:

The first term, as we see, is the first fraction; the first and second together give the second fraction, 22/7; the first, the second and the third give the third fraction 333/106, and so on with the rest; the result being that the series entire is equivalent to the original value.

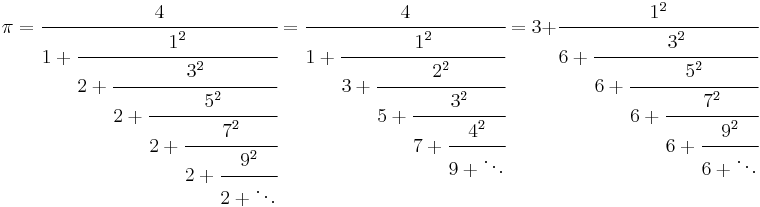

Generalized continued fraction

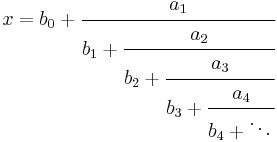

A generalized continued fraction is an expression of the form

where the an (n > 0) are the partial numerators, the bn are the partial denominators, and the leading term b0 is called the integer part of the continued fraction.

To illustrate the use of generalized continued fractions, consider the following example. The sequence of partial denominators of the simple continued fraction of π does not show any obvious pattern:

or

However, several generalized continued fractions for π have a perfectly regular structure, such as:

The first two of these are special cases of the arctangent function with π = 4 arctan 1.

Other continued fraction expansions

Periodic continued fractions

The numbers with periodic continued fraction expansion are precisely the irrational solutions of quadratic equations with rational coefficients (rational solutions have finite continued fraction expansions as previously stated). The simplest examples are the golden ratio φ = [1; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...] and √ 2 = [1; 2, 2, 2, 2, ...]; while √14 = [3;1,2,1,6,1,2,1,6...] and √42 = [6;2,12,2,12,2,12...]. All irrational square roots of integers have a special form for the period; a symmetrical string, like the empty string (for √ 2) or 1,2,1 (for √14), followed by the double of the leading integer.

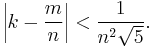

A property of the golden ratio φ

Because the continued fraction expansion for φ doesn't use any integers greater than 1, φ is one of the most "difficult" real numbers to approximate with rational numbers. One theorem[7] states that any real number k can be approximated by rational m/n with

While virtually all real numbers k will eventually have infinitely many convergents m/n whose distance from k is significantly smaller than this limit, the convergents for φ (i.e., the numbers 5/3, 8/5, 13/8, 21/13, etc.) consistently "toe the boundary", keeping a distance of almost exactly  away from φ, thus never producing an approximation nearly as impressive as, for example, 355/113 for π. It can also be shown that every real number of the form (a + bφ)/(c + dφ) – where a, b, c, and d are integers such that ad − bc = ±1 – shares this property with the golden ratio φ; and that all other real numbers can be more closely approximated.

away from φ, thus never producing an approximation nearly as impressive as, for example, 355/113 for π. It can also be shown that every real number of the form (a + bφ)/(c + dφ) – where a, b, c, and d are integers such that ad − bc = ±1 – shares this property with the golden ratio φ; and that all other real numbers can be more closely approximated.

Regular patterns in continued fractions

While one cannot discern any pattern in the simple continued fraction expansion of π, this is not true for e, the base of the natural logarithm:

which is a special case of this general expression for positive integer n:

Another, more complex pattern appears in this continued fraction expansion for positive odd n:

with a special case for n = 1:

Other continued fractions of this sort are

where n is a positive integer; also, for integral n:

with a special case for n = 1:

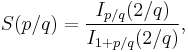

If In(x) is the modified, or hyperbolic, Bessel function of the first kind, we may define a function on the rationals p/q by

which is defined for all rational numbers, with p and q in lowest terms. Then for all nonnegative rationals, we have

with similar formulas for negative rationals; in particular we have

Many of the formulas can be proved using Gauss's continued fraction.

Typical continued fractions

Most irrational numbers do not have any periodic or regular behavior in their continued fraction expansion. Nevertheless Khinchin proved that for almost all real numbers x, the ai (for i = 1, 2, 3, ...) have an astonishing property: their geometric mean is a constant (known as Khinchin's constant, K ≈ 2.6854520010...) independent of the value of x. Paul Lévy showed that the nth root of the denominator of the nth convergent of the continued fraction expansion of almost all real numbers approaches an asymptotic limit, which is known as Lévy's constant. Lochs' theorem states that nth convergent of the continued fraction expansion of almost all real numbers determines the number to an average accuracy of just over n decimal places.

Pell's equation

Continued fractions play an essential role in the solution of Pell's equation. For example, for positive integers p and q, p2 − 2q2 = ±1 only if p/q is a convergent of √2.

Continued fractions and chaos

Continued fractions also play a role in the study of chaos, where they tie together the Farey fractions which are seen in the Mandelbrot set with Minkowski's question mark function and the modular group Gamma.

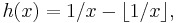

The backwards shift operator for continued fractions is the map  called the Gauss map, which lops off digits of a continued fraction expansion:

called the Gauss map, which lops off digits of a continued fraction expansion: ![h([0;a_1,a_2,a_3,\dots]) = [0;a_2,a_3,\dots]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/89681ecc87ecc413155afda307335c77.png) . The transfer operator of this map is called the Gauss–Kuzmin–Wirsing operator. The distribution of the digits in continued fractions is given by the zero'th eigenvector of this operator, and is called the Gauss–Kuzmin distribution.

. The transfer operator of this map is called the Gauss–Kuzmin–Wirsing operator. The distribution of the digits in continued fractions is given by the zero'th eigenvector of this operator, and is called the Gauss–Kuzmin distribution.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

The Lanczos algorithm uses a continued fraction expansion to iteratively approximate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a large sparse matrix.

History of continued fractions

- 300 BC Euclid's Elements contains an algorithm for the greatest common divisor which generates a continued fraction as a by-product

- 499 The Aryabhatiya contains the solution of indeterminate equations using continued fractions

- 1579 Rafael Bombelli, L'Algebra Opera – method for the extraction of square roots which is related to continued fractions

- 1613 Pietro Cataldi, Trattato del modo brevissimo di trovar la radice quadra delli numeri – first notation for continued fractions

- Cataldi represented a continued fraction as

&

& &

& &

& with the dots indicating where the following fractions went.

with the dots indicating where the following fractions went.

- 1695 John Wallis, Opera Mathematica – introduction of the term "continued fraction"

- 1737 Leonhard Euler, De fractionibus continuis dissertatio – Provided the first then-comprehensive account of the properties of continued fractions, and included the first proof that the number e is irrational.[8]

- 1748 Euler, Introductio in analysin infinitorum. Vol. I, Chapter 18 – proved the equivalence of a certain form of continued fraction and a generalized infinite series, proved that every rational number can be written as a finite continued fraction, and proved that the continued fraction of an irrational number is infinite.[9]

- 1761 Johann Lambert – gave the first proof of the irrationality of π using a continued fraction for tan(x).

- 1768 Joseph Louis Lagrange – provided the general solution to Pell's equation using continued fractions similar to Bombelli's

- 1770 Lagrange – proved that quadratic irrationals have a periodic continued fraction expansion

- 1813 Carl Friedrich Gauss, Werke, Vol. 3, pp. 134–138 – derived a very general complex-valued continued fraction via a clever identity involving the hypergeometric function

- 1892 Henri Padé defined Padé approximant

- 1972 Bill Gosper – First exact algorithms for continued fraction arithmetic.

See also

- Stern–Brocot tree

- Computing continued fractions of square roots

- Complete quotient

- Engel expansion

- Generalized continued fraction

- Mathematical constants (sorted by continued fraction representation)

- Restricted partial quotients

- Infinite series

- Infinite product

- Iterated binary operation

- Euler's continued fraction formula

- Śleszyński–Pringsheim theorem

Notes

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/135043/continued-fraction

- ^ Long (1972, p. 173)

- ^ Pettofrezzo & Byrkit (1970, p. 152)

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Periodic Continued Fraction" from MathWorld.

- ^ a b M. Thill (2008), "A more precise rounding algorithm for rational numbers", Computing 82: 189–198, doi:10.1007/s00607-008-0006-7

- ^ Paeth, Alan W. (1995). Graphic Gems V. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-543455-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=8CGj9_ZlFKoC&pg=PA25.

- ^ Theorem 193: Hardy, G.H.; Wright, E.M. (1979). An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (Fifth ed.). Oxford.

- ^ Sandifer, Ed (February 2006). "How Euler Did It: Who proved e is irrational?" (PDF). MAA Online. http://www.maa.org/editorial/euler/How%20Euler%20Did%20It%2028%20e%20is%20irrational.pdf.

- ^ "E101 – Introductio in analysin infinitorum, volume 1". http://math.dartmouth.edu/~euler/pages/E101.html. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

References

- Jones, William B.; Thron, W. J. (1980). Continued Fractions: Analytic Theory and Applications. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications.. 11. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 0-201-13510-8.

- Khinchin, A. Ya. (1964) [Originally published in Russian, 1935]. Continued Fractions. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-486-69630-8.

- Long, Calvin T. (1972), Elementary Introduction to Number Theory (2nd ed.), Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company

- Oskar Perron, Die Lehre von den Kettenbrüchen, Chelsea Publishing Company, New York, NY 1950.

- Pettofrezzo, Anthony J.; Byrkit, Donald R. (1970), Elements of Number Theory, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall

- Rockett, Andrew M.; Szüsz, Peter (1992). Continued Fractions. World Scientific Press. ISBN 9810210477.

- H. S. Wall, Analytic Theory of Continued Fractions, D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1948 ISBN 0-8284-0207-8

- A. Cuyt, V. Brevik Petersen, B. Verdonk, H. Waadeland, W.B. Jones, Handbook of Continued fractions for Special functions, Springer Verlag, 2008 ISBN 978-1-4020-6948-2

- Rieger, G. J. A new approach to the real numbers (motivated by continued fractions). Abh. Braunschweig.Wiss. Ges. 33 (1982), 205–217

External links

- An Introduction to the Continued Fraction

- Linas Vepstas Continued Fractions and Gaps (2004) reviews chaotic structures in continued fractions.

- Continued Fractions on the Stern-Brocot Tree at cut-the-knot

- The Antikythera Mechanism I: Gear ratios and continued fractions

- Continued Fraction Arithmetic Gosper's first continued fractions paper, unpublished. Cached on the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Continued Fraction" from MathWorld.

- Continued Fractions by Stephen Wolfram and Continued Fraction Approximations of the Tangent Function by Michael Trott, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Exact Continued Fraction for Pi

- Continued Fractions and Continuants at sputsoft.com

- a view into "fractional interpolation" of a continued fraction {1;1,1,1,...}

![x = [a_0; a_1, a_2, a_3] \;](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6382cc2d91f73d44f69895b6d2b3ea06.png)

![[a_0; a_1, a_2, a_3, \,\ldots ] = \lim_{n \to \infty} [a_0; a_1, a_2, \,\ldots, a_n].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/61e8d3912f012f1b1be348b7ffbf1c65.png)

![[a_{0}; a_{1}, a_{2}, \,\ldots, a_{n-1}, a_{n}, 1]=[a_{0}; a_{1}, a_{2}, \,\ldots, a_{n-1}, a_{n} %2B 1]. \;](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/db718cedfa322845dcaa74020824ec2e.png)

![[a_{0}; 1]=[a_{0} %2B 1]. \;](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/547cb7aadd150931bed7509ade7a238b.png)

![2.25 = 2 %2B 1/4 = [2; 4] = 2 %2B 1/(3 %2B 1/1) = [2; 3, 1], \;](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7b5a231dc9d5de628cb79a90856ae0c1.png)

![-4.2 = -5 %2B 4/5 = -5 %2B 1/(1 %2B 1/4) = [-5; 1, 4] = -5 %2B 1/(1 %2B 1/(3 %2B 1/1)) = [-5; 1, 3, 1]. \;](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6e331d39f962403fd86a8e1f4043bdc8.png)

![2.25 = \frac{9}{4} = [2; 4], \;](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3d8f2c12ea520aa1fa2375705fd9e2a6.png)

![\frac{1}{2.25} = \frac{4}{9} = [0; 2, 4]. \;](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e31b7959b8e322c1758a9830f36656b3.png)

![\left[a_0; a_1, \,\dots, a_{n-1}, x \right]=

\frac{x h_{n-1}%2Bh_{n-2}}

{x k_{n-1}%2Bk_{n-2}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2121d15f37eb60c326eb9df0b64ff328.png)

![\left[a_0; a_1, \,\dots, a_n\right]=

\frac{h_n}

{k_n}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/15b0b6545256be89c8c732a82ea531d7.png)

![\left[a_k;a_{k-1},\ldots,a_1\right] > \left[a_k;a_{k%2B1},\ldots\right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/60a0c4401e4ab0fff61df7d03d176968.png)

![\begin{align}

x &= [a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_{k-1}, a_k, a_{k%2B1}, \ldots ]\\

y &= [a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_{k-1}, b_k, b_{k%2B1}, \ldots ]

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8771e32d5b551a3dec4fb8e71f94f8ab.png)

![z(x,y) = [a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_{k-1}, \min(a_k,b_k)%2B1]\,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c94b9e9d731b073e91dbaf965d75b818.png)

![\begin{align}

3.14155 &= [3; 7, 15, 2, 7, 1, 4, 1, 1] = [3; 7, 15, 2, 7, 1, 4, 2]\\

3.14165 &= [3; 7, 16, 1, 3, 4, 2, 3, 1] = [3; 7, 16, 1, 3, 4, 2, 4] \,,

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/123f57e995a7a9d2c9e656dffacc90d3.png)

![[3; 7, 16] = \frac{355}{113} = 3.1415929\ldots\,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4abed417c3534ebb79d2ec986f24d5da.png)

![z = [a_0; a_1, \ldots, a_{k-1}, a_{k}, 1] = [a_0; a_1, \ldots, a_{k-1}, a_{k}%2B1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a1539c991b77f5450a5e418a90b8b5ec.png)

![\begin{align}

x & = [a_0; a_1, \ldots, a_{k-1}, a_{k}, 2]\mathrm{~and}\\

y & = [a_0; a_1, \ldots, a_{k-1}, a_{k} %2B 2]\,.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/087c9df2e9559f729d4e8ff76ec7a877.png)

![355/113 = [3; 7, 15, 1] = [3; 7, 16]\,,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bd4ed818c6b6ade410d69bc2c95166ca.png)

![\begin{align}

\,[3; 7, 15, 2] &= \frac{688}{219} \approx 3.1415525\mathrm{~and}\\

\,[3; 7, 17] &= \frac{377}{120} \approx 3.1416667\,.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5a3464666fc3379c9f720ad95fb89456.png)

![\pi=[3;7,15,1,292,1,1,1,2,1,3,1,\ldots]\,\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e8739565b01c9565b667f0e3a356e9fa.png)

![e = e^1 = [2; 1, 2, 1, 1, 4, 1, 1, 6, 1, 1, 8, 1, 1, 10, 1, 1, 12, 1, 1, \dots] \,\!,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/66ddfce7d2d19f05a2879a850ecd36f4.png)

![e^{1/n} = [1; n-1, 1, 1, 3n-1, 1, 1, 5n-1, 1, 1, 7n-1, 1, 1, \dots] \,\!.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5f13d31335a9523858362f121a2f126c.png)

![e^{2/n} = \left[1; \frac{n-1}{2}, 6n, \frac{5n-1}{2}, 1, 1, \frac{7n-1}{2}, 18n, \frac{11n-1}{2}, 1, 1, \frac{13n-1}{2}, 30n, \frac{17n-1}{2}, 1, 1, \dots \right] \,\!,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0683949bea5673e974674cd4006d503d.png)

![e^2 = [7; 2, 1, 1, 3, 18, 5, 1, 1, 6, 30, 8, 1, 1, 9, 42, 11, 1, 1, 12, 54, 14, 1, 1 \dots, 3k, 12k%2B6, 3k%2B2, 1, 1 \dots] \,\!.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8edb6388f7ed993f232e03c3e664eee0.png)

![\tanh(1/n) = [0; n, 3n, 5n, 7n, 9n, 11n, 13n, 15n, 17n, 19n, \dots] \,\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/34502897a8b91f0f63317e945cd05c4c.png)

![\tan(1/n) = [0; n-1, 1, 3n-2, 1, 5n-2, 1, 7n-2, 1, 9n-2, 1, \dots]\,\!,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b13814714b1f785a5e14c3b769b23e31.png)

![\tan(1) = [1; 1, 1, 3, 1, 5, 1, 7, 1, 9, 1, 11, 1, 13, 1, 15, 1, 17, 1, 19, 1, \dots]\,\!.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0aaa8f9d7d743168e2d967aa05fdce1f.png)

![S(p/q) = [p%2Bq; p%2B2q, p%2B3q, p%2B4q, \dots]\,\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/391336ee059ab587dec39619329ba523.png)

![S(0) = S(0/1) = [1; 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, \dots]\,\!.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/be43953da2efc6e4c733d61faaaac37a.png)